Canadense torna-se o primeiro remador PCD a atravessar os Grandes Lagos

Canadense Mike Shoreman torna-se a primeira pessoa PCD a percorrer os cruzar os cinco Grandes Lagos ... leia mais

Early 2020, paddlers from Brazil wrote yet another episode in outrigger canoe history. Marcelo Bosi and his son Rudah Bosi, on board of the legendary sailboat Kotik, became the first wa’a paddlers of the modern era to undertake an expedition through Antarctica.

The feat becomes even more important for Brazil due to the fact that “Manu Tere”, the canoe used, is a V3 produced by Life’s a Boat, 100% Brazilian made.

According to Marcelo Bosi it all started from a conversation with his friend João Paulo Barbosa. Renowned photographer and historian, João Paulo has works published in magazines such as National Geographic, among other renowned publications.

João was in Brasília exhibiting his work on his recent trip to Antartica.

Bosi, who was in town, met up with his friend. During a conversation, João Paulo suggested the idea of taking a Polynesian canoe for na expedition to the frozen continent.

“When João Paulo suggested the idea, I became instantly interested, but, at the same time, I questioned how were we going to accomplish this”, says Marcelo Bosi.

João then suggested a conversation with the captain of the Kotik sailboat, Igor Bely, who spent a good part of his life sailing in the South Seas and has made several expeditions alongside Beto Pandiani, one of the greatest ocean crossing sailors in the world.

The fact that marks the 200th year since Antartica was was first sighted in modern era served as na incentive for the expedition.

However, reports narrated in a Polynesian myth tell us that a Maori navigator from Raratonga would have sailed his canoe through the Antarctic region long before, in the 7th century, at about the same time that Aotearoa (New Zealand) was discovered by the Polynesians.

The stories, passed down from generation to generation, talk about the achievements of Polynesian navigators who would have seen a cold land, covered by mountains of ice and inhabited by exotic animals.

For the photographer, the presence of a Polynesian canoe there, paddling through those icy waters, would also be a manifesto. An ancestral claim for more respect for a continent increasingly occupied by rich countries and large corporations.

The expedition would serve, therefore, to remember that Antarctica is a free continent, without belonging to any nation, and must remain so, as a good of all humanity.

Marcelo Bosi says that the second step was to raise funds for the expedition.

They came up with a project and presented it to several producers. The idea would be, in addition to the photos, to produce a documentary about the trip.

A producer showed interest, however, failed to raise the necessary funds.

However, captain Igor Bely kept the invitation and Bosi decided to face the challenge, but with some changes:

“In the beginning, we thought about taking an OC4 and two more paddlers and the entire film crew. As it was not possible due to lack of funds, we chose to bring a V3. We would paddle with my 14 year old son Rudah and João Paulo”, says the paddler.

Brazil played an important role in the first phase of scientific exploration in Antarctica, as it served as a stop for supplying ships traveling south.

In recognition of this logistical support, some geographical accidents, such as islands and mountains, were named after important personalities of the time.

João Paulo, a profound scholar of the history of Antarctica, wanted to take advantage of the expedition to bring attention to these Brazilian toponyms (proper names of places and their origin) in the Antarctic continent, which are very little known and spoken of in Brazil.

The idea would be to circumnavigate the Pernambuco and Sampaio Ferraz Islands, in addition to visiting mountains such as the Montes Rio Branco and the Alencar peak.

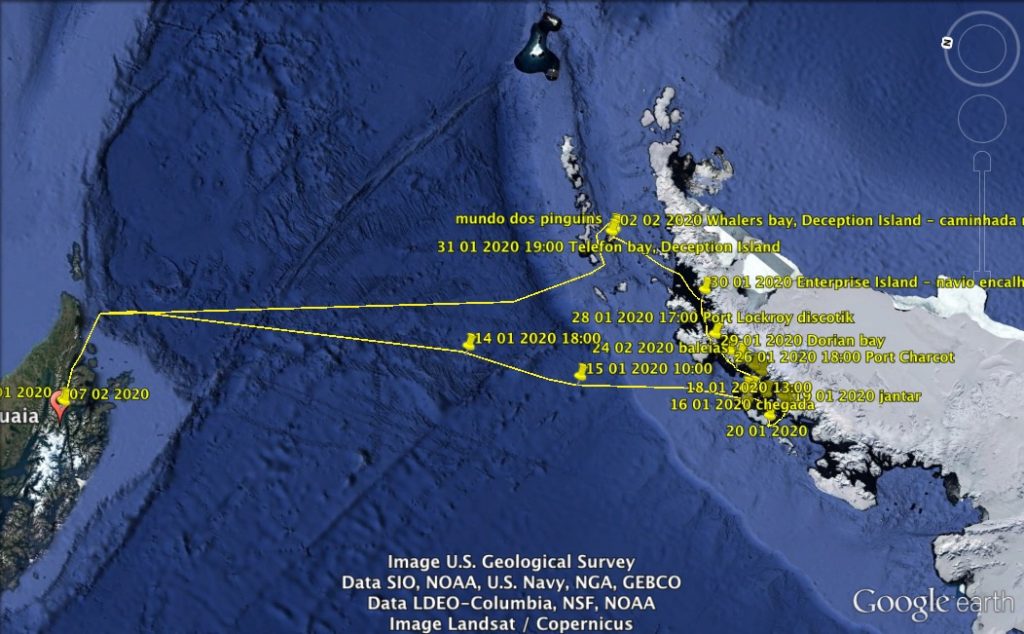

The expedition began in January. In total, 28 days embarked, departing from Ushuaia, in the extreme south of South America, towards the icy continent.

After five days of sailing, the Kotik crossed the Drake Strait, officially arriving in Antarctica.

This strait is known to be one of the worst navigation points in the world, however, the conditions during the crossing were very favourable, and the captain took the opportunity to continue heading south, exploring less visited areas.

The first strokes were done very carefully. The visibility was not very good and the winds, a little strong, demanded attention all the time.

If the canoe hullied, falling into that freezing water would take the body to a state of hypothermia with an imminent risk of death if a rescue was not made in time.

“We use dry suits for paddling, which is the most suitable suit for this type of condition. Without them, it would be practically impossible to do that because of the cold, as well as being very imprudent, since dressed like this would already be a risk to fall into the water, without these clothes, it would be practically certain death due to hypothermia ”, reports Marelo Bosi.

Marcelo says the paddling lasted about 40 minutes. Even equipped with dry suits, which kept the body well warm, the lack of specific gloves ended up hampering the action.

“I bought mountain climbing gloves believing that they would solve the problem, however, with the movement of the stroke, as they wetted, the hand would freeze and we were forced to stop ”, he reveals.

Even so, the strokes were epic, culminating in an encounter with whales that lasted more than an hour:

“It was unforgettable. We anchored the sailboat in one of the bays with the largest population of whales in Antarctica. We put the V3 in the water and approached them carefully. The adrenaline was strong since we were in a totally wild environment, but we gradually relaxed and enjoyed the experience ”, he says.

The whales were also gradually approaching and interacting with the visitors:

“They are extremely intelligent and kind. They approached, accompanied and interacted with us. It is difficult to explain in words what we experienced that day. Unforgettable! ”Reveals Marcelo Bosi.

In the canoe were: Marcelo, Samanta, the captain’s wife, and Rudah, who had just turned 14.

“It was a rite of passage for Rudah. For me, as a father, it was great to have this experience with my son. A unique opportunity. From the first contact with wildlife; seals, penguins on the islands we landed, to the experience paddling with the whales. It was something that strengthened the bonds between father and son. A memory that we will always carry with us”, he ponders.

And what changes for a va’a paddler after an experience like this? Marcelo Bosi says:

“My relationship with outrigger canoeing took on a much greater dimension after that expedition. Something that goes far beyond competitions. I feel like I was able to experience what these Polynesian explorers felt when navigating unknown and inhospitable regions, where you feel like a tiny part integrated into a whole.

We spent two weeks without seeing any other vessel. We paddled through places where nature is still in harmony and far from the negative impact caused by man. There is also a deep feeling that it must all be preserved and maintained as is.

We need to show that there is something much bigger than a medal or a title, values that are much more important and with a greater meaning than being attached to ephemeral conquests.

In addition, the desire to seek new challenges and different experiences emerged very strongly in me after this expedition, and I intend to invest in new projects.

My relationship with wa’a changed forever after that trip.”

Marcelo Bosi says he is now looking for supporters to put this experience in a book aimed at children and young people.

He also studies the making of an authorial documentary with the material captured during the trip. Even with a lean team to record the trip, there are many high-quality video images, including drone footage.

Anyone interested in a being part of these projects can contact Marcelo Bosi by e-mail marbosi@gmail.com, Instagram @marbosi and Facebook / RudahnaAntartica.

* Text translated into English under the supervision of Ronald Williams, Brazilian Wa’a pioneer